Indian Reservation Explained – What It Means for Jobs, Education and Everyday Life

When you hear the word “reservation” in India, most people think of the government’s effort to give certain groups a fair shot at jobs, schools and politics. It’s a form of affirmative action that tries to balance historical disadvantages faced by Scheduled Castes, Scheduled Tribes, and Other Backward Classes.

In plain terms, a reservation is a quota. If a college has 100 seats and the law says 15% must go to SC candidates, then 15 seats are set aside for them, no matter what the overall competition looks like. The same idea applies to government jobs, where a slice of the total posts is earmarked for these groups.

Why the Reservation System Exists

The roots go back to the Constitution of 1950. The framers wanted to lift millions out of poverty and social exclusion that the caste system had entrenched for centuries. By reserving spots in education and public employment, they hoped to create a new middle class from communities that had been stuck at the bottom.

Supporters argue that without these quotas, the playing field stays uneven. They point to data showing higher dropout rates and lower literacy among reserved categories, which means a level‑playing field doesn’t happen on its own.

Critics, however, say the system can breed resentment and that merit gets ignored. Some suggest a shift toward economic criteria rather than caste alone. The debate shows up in every election, court case, and college admission season.

What It Looks Like Today

At the moment, the reservation percentages are roughly 15% for SC, 7.5% for ST, and 27% for OBC in central government jobs and higher‑education institutions. Some states add their own numbers, especially for tribal groups. Private companies aren’t bound by law, but many adopt similar policies to attract talent and meet corporate social responsibility goals.

Implementation varies. In top engineering colleges, you’ll see separate merit lists for each category. In a government office, the hiring panel checks the applicant’s caste certificate before confirming the vacancy. The process can be bureaucratic, and errors sometimes lead to legal battles.

For a regular person, the reservation system shows up when you apply for a college seat or a government job. You’ll be asked for a caste certificate, and if you belong to a reserved group, you’ll be placed in the relevant quota pool. If you don’t, you compete in the open category.

What does this mean for everyday life? For many, it’s a lifeline that opens doors to better jobs and higher education. For others, it’s a source of frustration when they feel the system is uneven. The key takeaway is that reservations are a policy tool, not a permanent solution. The goal is to create a society where everyone can succeed without needing quotas.

Looking ahead, the conversation is shifting toward how to phase out reservations while keeping the gains. Ideas include improving primary education quality, offering scholarships based on economic need, and increasing private sector participation. Whatever the future holds, understanding how the reservation system works today helps you navigate the opportunities and challenges it brings.

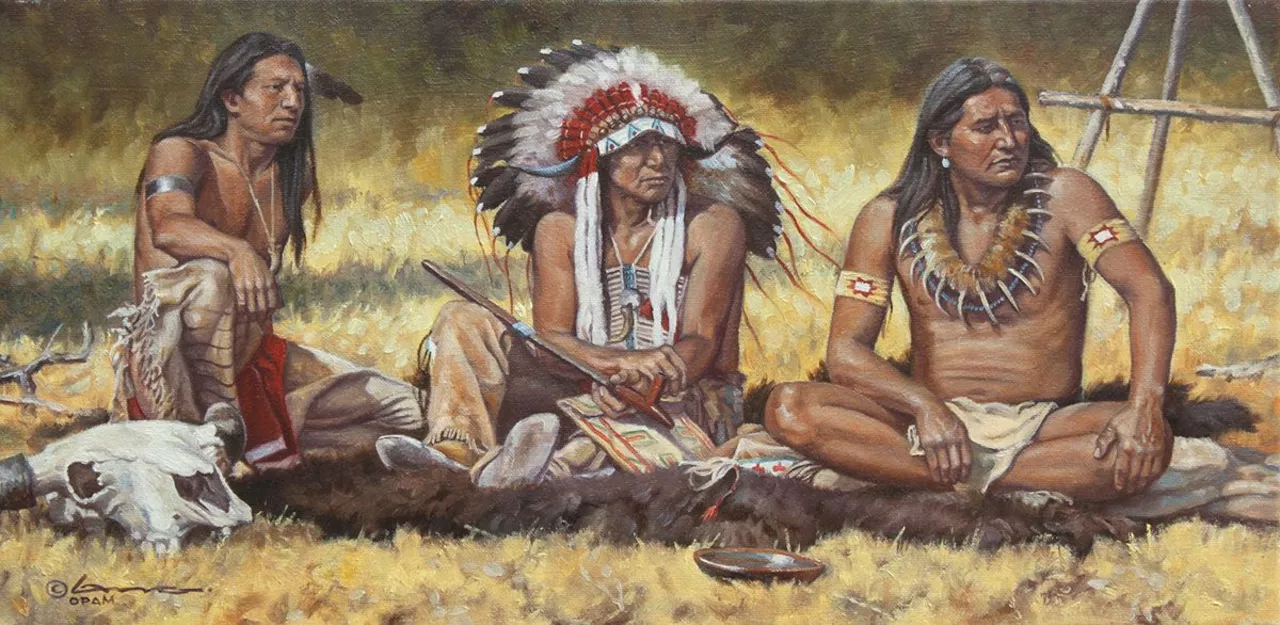

What is it like to live on a Native American Indian Reservation?

Living on a Native American Indian Reservation can be a unique and rewarding experience. The sense of community, culture, and history shared by the people living on the reservation is unlike any other. Residents can enjoy the beauty of nature, traditional ceremonies and activities, and a close connection to the land. Life on the reservation can provide a sense of belonging and connection to a people and a place that has been around for many generations. Despite challenges, the community of a Native American Indian Reservation can be a place of comfort, strength, and support.

More